PC

Conway: Disappearance at Dahlia View has consumed me, this week. From White Paper Games, who’ve previously made the not-quite-good-but-fascinating Ether One, and the flawed-but-interesting The Occupation. With Conway, I feel this ridiculously talented team have finally hit their stride, even if that stride is a very, very slow one.

Conway is about a missing child, presumably kidnapped, and the small, gated community in 1950s England in which the incident occurred. You play as the titular Robert Conway, a retired private detective, confined to a wheelchair, who is determined to solve the mystery.

If the setup sounds particularly Agatha Christie-ish, I don’t think that’s any mistake. While there’s no murder, this is very much one of those confined stories of a defined collection of possible suspects, and the insider busybody who’s nosily investigating them all. What’s so interesting here, however, is that the story leans far further into questioning whether such a thing is even vaguely appropriate than Miss Marple ever worried.

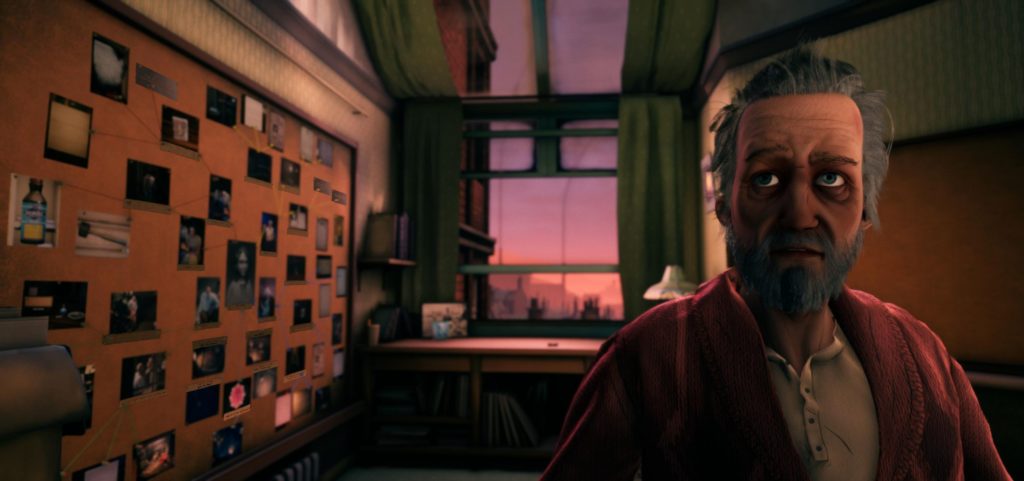

First and foremost, the game looks and sounds incredible. The art is somewhere between Dishonored and The Wolf Among Us, this unplaceable-yet-so-British location rendered in enormously intricate detail, featuring hundreds of incredibly well-modelled everyday objects, and with the caricature characters displaying a boggling array of unique animations, facial expressions, and even lip-syncing. This is then bolstered by the best voice cast I’ve ever heard in a British game, and one of the best in any game at all.

Conway is voiced by Nathaniel-Jorden Apostol, who no, you likely haven’t heard of, since he’s the game’s audio director and composer. (And what a score he’s composed here.) Yet his voice, remarkably similar to the implausibly named Jonathan Cake, is spellbinding. His calm, measured delivery is a joy in every scene, and I now want him to read every audiobook ever. I cannot over-stress just what an impact Apostol’s delivery has on the entire experience.

But he’s not alone. Every voice here is fantastic, and I say this as someone who usually cringes at British voices in games. There’s something… tepid about them, a lack of conviction, like everyone just got done recording an episode of The Archers, and is exhausted from the effort. Not so here, the whole cast really giving life to the brilliantly animated citizens of the townhouses.

As for what you actually do, this plays mostly as a third-person adventure game, you controlling Conway’s wheelchair with WASD, and interacting with objects and areas with an F. (Or with the controller, or… both, but we’ll get to that.) It’s about exploring, finding objects, solving puzzles to reveal (rather too inevitably) keys, all in pursuit of any information you can gather on each of your neighbours.

Conversations are mostly automated, but the game’s no worse for that. Clicking through all the possible dialogue options in adventure games might give some a greater delusion of involvement, but it’s silly. As it happens, here when you do get a dialogue choice, it’s usually one of three or four, and closes down the other routes – far more compelling.

The very long game is broken into chapters, of sorts, with Conway investigating a different neighbour. While this begins with a very Rear Window-esque staring through people’s windows, it eventually means getting inside their house, and it seems the laconic former detective has few qualms about how he achieves this. (Also, it means I’m still waiting for my dream full-on Rear Window mystery-solving video game.) This is the first sign of the interesting moral framework in which the game operates. You know, and Conway knows, that what he’s doing isn’t really OK. And not least when your poking your nose through their underwear (sometimes literally) reveals personal secrets and scandals at best tenuously relevant to the missing girl.

This morality is further complicated by Conway’s relationship with his adult daughter. She’s a police officer, assigned to the case, and has made her father swear to her he won’t get involved. But finding himself promising to the missing girl’s father that he’ll bring her home, he’s immediately – and very deliberately – breaking that promise.

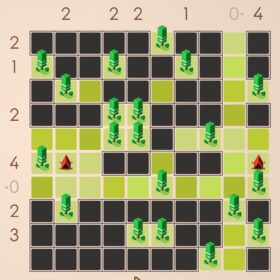

Between these forays into others’ private lives, Conway pieces together evidence gathered and photographed on his investigation board, which unashamedly has you stringing clues together with red string across a pinboard. It’s enormously satisfying to get right, and as with most aspects of the game, leans in to this meta-narrative of the dubiousness of private investigation. Without due process, it’s very easy to see patterns, and without operating within the boundaries of the lawful process, you can make… leaps.

I’ve held off a long time, because I really want to communicate just how much I’ve enjoyed and been impressed by Conway, but there are some serious problems too. Most of them are technical, the game feeling like it really needed a couple more months in the oven before release. While Conway’s cumbersome wheelchair is often the point (it really sucks to live in an able-bodied world when you’re stuck on wheels, and especially so in the 50s), it’s also sometimes just a mess. Far too often you’ll get stuck on the corner of a table, or be unable to see the path in front of you because the camera is bizarrely placed.

I also had it just break down a few times, differently each time. At one point the game stopped showing me any on-screen prompts, meaning I had to guess where I could interact, until I restarted. At another, all the prompts appeared, but I couldn’t interact with them. This is then exacerbated by the completely ridiculous lack of a save option (I guess you could savescum those few conversations where you have choices, but I can’t see why you’d want to), and the oddity that reloading the game has you reappear at the beginning of a scene, but have the objects you’ve collected, or puzzles solved, sometimes remain that way.

Controls are also a bit of a mess. While for the most part I was fine with either controller or mouse and keyboard, the game has some very unwelcome lock-picking puzzles, and here I’d say the controller was useless. But then there was an atrocious sequence in which you have to dislodge some keys with a pool cue, and the mouse made this unbearable.

Oh, and dear God it’s slow. For the most part, I really appreciated that. It’s meant to be, the deliberate pace in the game’s bones, from the limited movement of a hand-turned wheelchair, to the nature of the older man’s calm, methodical approach. But that’s not an excuse for the opening, which is insultingly dull, beginning with its unskippable opening vanity cards, crawling toward a menu screen, then astonishingly making you sit through the same unskippable vanity cards yet again. By the time anything happened, I was yelling at the screen to get on with it, and pretty close to just quitting out. I’m delighted I didn’t, but for goodness sakes.

Some of the mistakes White Paper have made in their previous two games are here again. They’re over-ambitious, aim beyond their means, and try to include far too many extraneous details without getting the core completely correct. But at the same time, I can see why, I can see what they’re aiming toward. I really think they’re going to get there, and in Conway, a lot of it is achieved. Heck, this is a game with a jukebox in one location, that is entirely uncritical to the plot, that has a whole bunch of fantastic tunes on it to listen to as you investigate. And a darts game, for no reason at all.

In so many other ways, it blew me away. I haven’t even mentioned the audio direction, which isn’t something that ordinarily stands out to me in a game, but here was absolutely compelling. Voices coming from far off, sudden footsteps to the right that I’d swivel around to see.

I was slightly disappointed by some aspects of the ending, not really delivering on the consequences of Conway’s actions throughout the game. While one aspect of the story does get remarkably dark, another is not nearly bleak enough. And I guarantee you’ll be left shouting one particular question at the screen when the credits start to roll. But it’s all worth it.

There’s so much ambition here, and it’s delivered with such brave pacing, within a world that competes with Dunwall on looks, and some of the best voice acting I’ve ever encountered. While it occasionally frustrated me, if nothing else, Conway’s soothing, mellifluous voice saw me through.

While Conway is currently only available on PC, it’s due to arrive on consoles next year.

- White Paper Games / Sold Out

- Steam, Epic, GOG

- £25/€30/$30

- Official Site

All Buried Treasure articles are funded by Patreon backers. If you want to see more reviews of great indie games, please consider backing this project.

Bought this on your recommendation and I’m so glad I did, because I love a good atmospheric mystery. I fully agree with everything here. (That voice acting! The sound design on the whole is nice and chunky and I like that.) Game’s been patched since this review, but I didn’t have a bit of trouble using the wheelchair, never got stuck. And the pacing didn’t bother me a bit. Personally I’d describe it as mannered rather than slow, and I enjoy the atmosphere that pacing helps create.

But it does the two thing I hate most in investigation games. I love this genre so much and I very much recommend this game, but John, I can’t lie, I do have a pickle up my butt about this stuff.

First, well over half of the hotspots and items don’t actually do anything. That’s understandable when part of the gameplay is figuring out which clues are relevant and which can be ignored. But surely that’s what the investigation board with the bits of string is for. Conrad already magically knows which bar of soap or note he needs to take a picture of for his board, and that’s just fine with me, so why do I have to pick up and rotate and poke everything that isn’t a clue as well? I don’t get anything out of fiddling with every cup and and twirling every apple. In a game that’s already quite languid and fiddly (by design, and I approve) you don’t want to add a ton of extraneous fussing about. It just doesn’t help my experience to be able to turn on all the taps. I would have been perfectly happy taking it on faith that the neighbors have working taps. We’re here to look for a missing child, I remind you. LA Noire had this problem too and honestly, it’s tedious to me, and I have never seen a full-throated defense of this style of investigation gameplay. It’s like we’re just stuck with it because no one knows what else to do. This is the modern version of pixel hunting, and it wasn’t fun in the 90s either. (This is why, as much as it pains me to say, I’m becoming more and more convinced that purely text-and-menu based investigation games like the Phoenix Wright series have the right of it. I’m convinced the main gameplay element in this genre is just *thinking*. PW doesn’t feel like a visual novel because you’re constantly doing mental labor and putting in effort. Mystery stories absolutely need to maintain tight control over their pacing, and all this fiddle-me-do absolutely does not help with that.)

Second, I do not understand why in the last decade or so game designers became convinced that swiping and waving my mouse all over my desk like I’m Harry bloody Potter would improve my experience. (Is it Amnesia that did it? That’s the first time I remember being annoyed by this nonsense.) Is it supposed to be more immersive when I have to swipe my mouse three feet across my tiny desk to open a cupboard? (To be fair, the accessibility options let you turn off all that swiping and tapping and lockpicking wank, thank god)

Apart from my own personal nitpicks about the genre as a whole, it bugs me a little (but not a lot) that Conway, a professional detective I’ll remind you, doesn’t think to put the stuff he’s fiddling with while he’s breaking and entering back where he found it. It kind of undermines his anguish at betraying his daughter’s trust (very well played and believable, I should add) when he YOLOs through his neighbors’ homes without even a token attempt to hide his tracks. Very odd. And not the only time the plot requires Conway to do something counter-intuitive. (“Do you have proof of an intruder?” ask a character. “Yes!” says I, having moments before taken a picture of an intruder. “No,” says Conway. )

Oh, and White Paper, listen here and listen well; if I’m playing an investigation game, and I’m in a bathroom, and there’s a mirror centered on the screen with a clearly labeled hot water tap underneath even though other taps aren’t labeled in that way, there had better be a spooky message revealed by the steam. I just did all that on pure muscle memory and poof. Nothing. White Paper, you got it wrong and I’m telling your mom.

Person from the future here – loved this take. I agree about the mirror message. Happen to have a link to a plot/gameplay breakdown?