A Familiar Fairytale has one goal: to show non-dyslexic players the experience of reading through dyslexic eyes. Essentially just a story to read, this is an extraordinarily effective achievement that could only ever be delivered through a game.

I’m fortunate not to be dyslexic. My issues with reading only come through a lack of concentration, quickly losing focus of the words I’m looking at and thinking about something else, often having to repeat paragraphs to take in what they’ve said. But when my eyes scan the words, they filter to my brain correctly. And while I’ve given thought to the difficulties of dyslexia, and even at one point helped a dyslexic kid learn to read, I’ve never been able to meaningfully empathise with the experience. Assuming A Familiar Fairytale is as authentic as it appears to be, I can now get a lot closer to doing so.

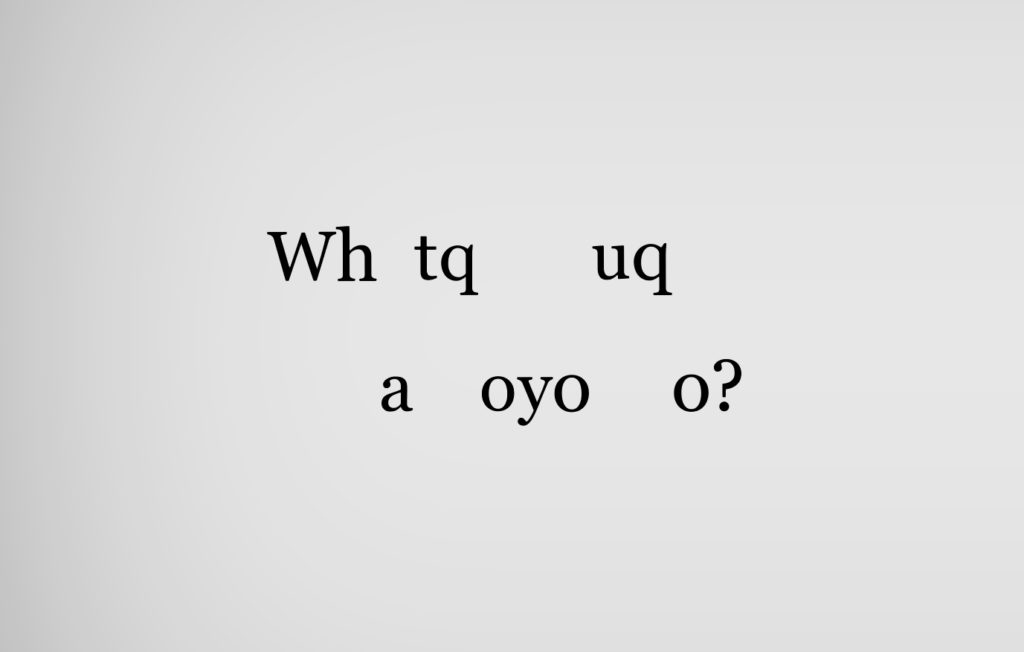

In each short chapter, the text appears on the screen in a variety of mangled, muddled and agitated ways. In the first chapter the words have no spaces between them, shifting up and down between lines at any point, while they jiggle about frenetically over a flickering background. (Flickering background warning, obvs.) In the second this is made more complicated by various letters being swapped with one another too, a ‘q’ for a ‘d’ or a ‘b’ perhaps, increasing the challenge of parsing the text.

At the same time, the game occasionally asks you to make one of four choices, equally difficult to read, but now with a timer ticking down far too quickly to be able to properly interpret them all. You’re forced to estimate, hope you’re picking a good option, only finding out after. And gosh, yes, here I think the empathy is at its most effective: the panic of not being able to read well enough, to not feel equipped to cope with the words, and a pressure from outside to just get on with it.

I immediately began reading the sentences out loud, to help me try to fathom them. And I then heard my voice, the stilted, question-tinged tone of an unconfident child who’s reading in front of a class. Following the content of the story I was reading became secondary to just being able to read the words that made it up, and sense was quickly lost in the process.

“But the… but… but he seemed…”

“You start off feel… You start off feelin… You start TO feel better!”

Sometimes I just got completely stuck, and felt helpless.

“You cautiously dro… broc… droq…?”

At one point I read the word “chandelier” with a hard “ch” start, a mistake I’d never otherwise make, one I might get laughed at were I to do it in company. In fact, the more I read, the more conscious I became that my wife downstairs might hear me and think I were going mad. I became more and more self-conscious about the act of reading.

In the first chapter your character’s mother gives you a series of instructions to follow, delivered in these jumbled sentences, and then later you’re required to remember them – and goodness me, simple directions are nightmarishly difficult to recall when they were given in such a form. I’ve no idea how much my brain relies on recalling the actual text in such circumstances, but it felt like vital elements just didn’t get taken in.

By chapter 5 I was struggling so much that at one point I gave an exasperated sigh, and recognised the sound right away. It’s the same noise my five-year-old makes when he’s had enough of trying to sound out letters to fathom words, as he learns to read for the very first time. While there are no signs of dyslexia in him, it’s all still completely brand new, and decoding the symbols is a mental effort that I keep forgetting to understand. “It’s just looking at words!” I think to myself, as he’s flopping his shoulders like a teenager, not wanting to carry on after a couple of pages. And now here I am, a literate adult, making that same noise, wanting to give up on the game rather than carry on, because it’s just too hard to keep battling against the struggle.

Qy the end, the worqs might qe rearranging themselves on the qage, lines shuffling uq and qown in columns, shifting over three lin es, orall run toge ther with ‘q’ reqlacingagooq numqer of letters.

It’s exhausting. That it’s a story means you’ll want to read to the end, but doing so requires a really concerted effort. Which is, obviously, the point. It’s an extremely effective window into the routine life of those with dyslexia, and has very quickly revealed to me how much I don’t take that seriously enough. The idea that the whole world would be encoded behind these shifting, frustrating, bemusing glyphs is utterly overwhelming, a realisation that’s a complete “well duh” for millions of people.

It remains a tough call to pay for, I’ll agree. But at only £2, it’s a fairly negligible sum to educate yourself in an extremely productive way. Or maybe passive-aggressively purchase it for everyone you know who doesn’t take dyslexia seriously.

- Alastair Lowe, Lowtek Games

- Steam, Itch, Android

- £2/$3

- Official site

All Buried Treasure articles are funded by Patreon backers. If you want to see more reviews of great indie games, please consider backing this project.

This sounds great. I’m not dyslexic, but this strongly reminds me of my ongoing attempts to learn Chinese. I’m not sure I wish to force myself through the experience in my spare time, when I’m already forcing myself through a very similar experience in my… spare time.

That was quite a struggle, but an interesting experience