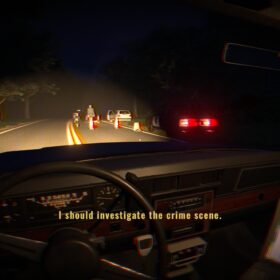

Still There is a game about grief. But no, wait, come back. Because goodness knows, yes, there are far too many of those in recent times, invariably weighted with their own crassness. Heavy-handed, cloying, or perhaps worst of all, about only grief, as if it’s a state of being that exists in isolation. Still There, while still tripping up here and there, is a much more nuanced approach, that remembers to also be about something else: being stranded on a remote space station, patching it up as it falls apart, with only an impudent AI for company.

This is the story of Karl Hamba, a divorcee whose marriage broke down after a tragedy. Which is pretty much why he accepted this most remote and lonely of positions, agreeing to monitor the space lighthouse Bento, in the year 2432. He’s tired. He’s pretty much done. But he has the routine drudgery of his job to keep him going.

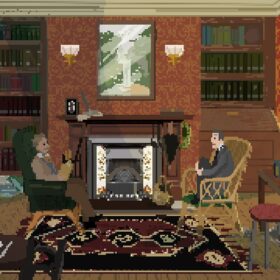

It’s intriguingly presented. While the game’s set in essentially a single screen – you’re in the centre of a tiny circular pod, scrolling the screen around you to look at each area – it plays like a point-and-click adventure. Complete with inventory, dialogue choices, and puzzles to solve. And my goodness, what puzzles.

When I first looked at the contents of the instruction manual found amidst a wall of switches, lights and ports, I thought it was a gag. “Ah ha ha, yeah, sure, I have to fathom this.” I had to fathom this.

In Still There, when something electronic breaks down on your pod you are going to be juggling circuit boards, wires, elaborate arrays of switches, the manual’s opaque diagrams, and the somewhat helpful advice from the AI, Gorky. Jumpers are arranged on nodes, satellites are hacked, air recyclers are re-routed, arguments are had. Sometimes these appear to be – to my non-electronic-brain’s understanding – reasonably authentic. Other times they become rather obviously contrived puzzles. But then there’s a reason the Bento comes equipped with a “Suspension Of Disbelief” device, that you’re warned is essential to stop the ship from simply disappearing from existence. It’s a nice, wry remark, and taken on board.

But it’s not all disasters. There’s plenty of everyday life to get through along the way, a combination of daily chores (if you want coffee, you’re going to need to recycle wee) and routine tasks to complete. The radiation levels of nearby constellations must be measured, systems must be checked, the on-board iguana-thing must be fed. In fact, you have enough down-time to play a game of chess with Gorky, and yeah, they’ve implemented a full chess game into this, and it whooped my ass.

And with all that time comes space for Karl’s thoughts, and his struggles, played out at first in both his conversations with the distinctly unsupportive Gorky, but also in his increasingly bizarre dreams. And then comes a strange signal on the radio.

I don’t want to go into any further details about the story, because that opening set-up is plenty, and the rest is the very point of playing. So instead I’ll talk about how really surprisingly tricky it is.

I mentioned the complexity of the machinery and mechanisms, and it’s with these that the game offers its meatiest challenges. Big pod-wide disasters have you scrambling to fix various elements, in the correct order, juggling intricate logic puzzles to do so (there’s no actual time pressure, despite the game so convincingly making it feel as though there should be). And thankfully, it knows how meaty they are. At the game’s hardest moments there’s a button of shame that pops up, which when pressed will “simplify” the situation. And it really does. I shall confess to having had to press it at one point, when just utterly stumped, and it did some really smart stuff, removing a bunch of the buttons involved, redesigning the entire challenge into a That Puzzle For Dummies mode.

Which is technically just so impressive. But… I didn’t really like it. I didn’t want a simpler puzzle, I wanted another hint. While Gorky will often outline what needs doing in clearer terms, there are at least two occasions in the six-hour game that I really wanted another prompt. Reducing the challenge to perfunctory was particularly unsatisfying, but for one crucial aspect: it ensured I could keep on playing.

Yet what most stood out for me amongst all going on here was the writing. And for a short while at the start, I really didn’t think that was going to be the case. In the opening moments there’s a bunch of really rather desperate references to porn, along with a (censored) nudy picture on the kitchen fridge. It seemed for a while like it was going to be a 13-year-old’s perception of “adult”, which was off-putting. But making it all the more strange, it’s quickly abandoned, the game getting on with being an adult’s perception of “adult” – grown ups talking about grown up stuff.

This it does so very, very well. There is some really nice writing in here. Here’s a lovely moment very early on, that while not DAZZLING, is just so effortlessly readable and interesting, in a way games just aren’t.

“The truth is I’m here to get away from myself. People say that when you travel you can be a different person, but that never lasts. Space is different. You’re truly, essentially alone out here. Remove any living presence around you and the self-deprivation is complete: nobody can perceive you.

After a while you stop perceiving yourself too.”

It does start getting a bit heavy-handed toward the end. I could have done without a particular moment in the final sequence that certainly ticked off “cloying”. But I forgive it, because there’s just so much here that’s so much better.

This is the work of just three people, Italian indie team GhostShark, who previously created the wholly different multiplayer FPS Blockstorm. They’ve got some range.

So while I wish there were better clarity about some of the puzzles, I’m so impressed with the implementation of the ‘simplification’ option. And while I wish the ending could have been a bit more subtle, I’m just blown away by the maturity with which this game discusses grief. And if for some silly reason you didn’t like any of that, it’s still got a really good chess game stuck in there!

- GhostShark, Iceberg Interactive

- GOG, Steam, Switch

- £11, $15

- Official site

All Buried Treasure articles are funded by Patreon backers. If you want to see more reviews of great indie games, please consider backing this project.

This convinced me to wishlist the game, I do love trying to figure out machines and devices in games like this, it’s very my asthetic.