PC, Mac, Linux

We need to invent a word for the sorts of games where talking about what makes them so interesting ruins the experience for anyone who hasn’t played. I want to write about Slender Threads to an audience of people who’ve already played it, discuss the intriguing way it deals with a specific aspect of point-and-click adventures, and how involving this as a narrative device allows it to speak to such matters without the usual recourse to parody or tedious archness. But we can’t do any of that in a review!

There is, I think, one aspect revealed very early on that we can divulge without taking too much away, but if you’d rather go in pure–as I had the luxury of being able to do, and you should too–then here’s everything you need to know before buying: This is a lovely adventure game, with stunning voice acting, beautiful art, strong writing, fun puzzles, but one with overly simple puzzles, yet too often leaves things unhelpfully vague about how to proceed. An in-built hint system takes care of that, but a bit more focus would have helped. It’s also one with a surprising darkness scattered throughout its breezy silliness that gives a bit of bite. I reckon you should buy it! Right, no one should read the rest of this before playing. But let’s discuss some themes.

A constant aspect of point-and-click adventures is the cavalier way in which protagonists approach the world. Morality is rarely in play, as characters steal, cheat, lie and manipulate to achieve a goal, whether that’s lying to a security guard to enter a building, or tricking an elderly lady into handing over her false teeth. You know the sort of thing. The puzzle is prime, as puzzles are barriers to progress, and progress is how we experience the narrative. This amorality of player characters is usually handled by either making the individual a cretin, or by fourth-wall-breaking references, and both are very over-used. Loveable idiots are far harder to write than idiot-idiots, and too many games just resort to writing someone who’s cruel. Meanwhile, winking to camera as if engaged in a satirical escapade is so overdone as to be a trope deserving of its own tired self-referencing.

Slender Threads does something far more interesting, and while it’s fair to say that this is–metatext stripped away–a fairly ordinary adventure game, it’s this narrative complexity that makes it so engaging. So as much as you’re absolutely winning a flower arranging contest by sabotaging the other entries by the sweet old ladies, purely so you can steal a gas mask–the most adventure gamey things imaginable–at the same time you’re aware that your actions are meaningful in a way that will make you feel… gently uncomfortable? Is that a thing? It’s how I felt.

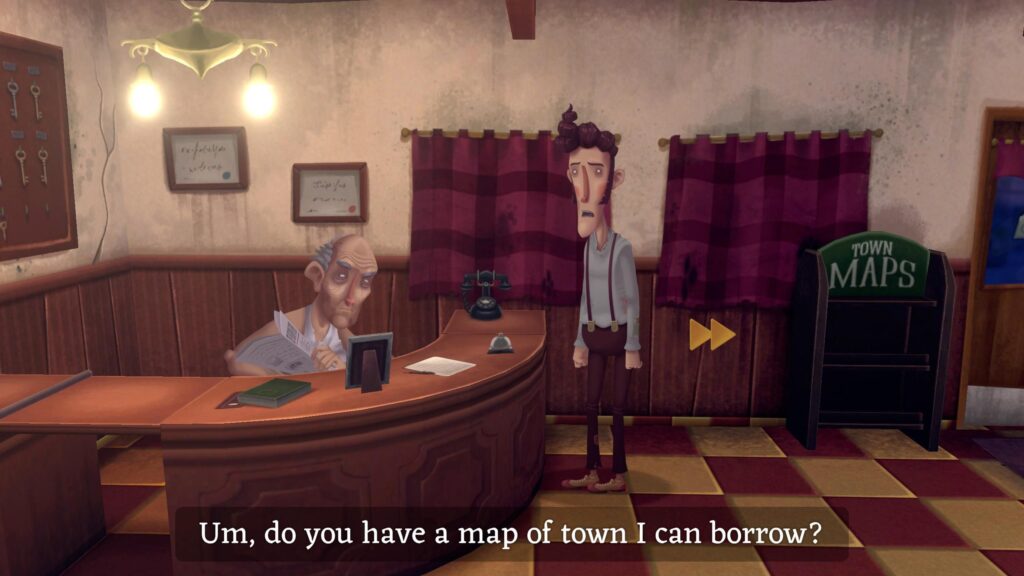

In Slender Threads, you play Harvey Green, a wannabe writer in, perhaps, the 1950s? (it’s ambiguous), making a living as a traveling book salesman. You show up in a small American town, shack up in the one hotel, and head out into the early evening. You’ve been told there’s another aspiring author in the building down the road from your hotel, Oswaldo, and as you walk past the door you hear a radio playing a mystery drama, but one that mentions your name. Heading inside you find an abandoned room, and a puzzle that hints you should look under the floor. There you find a key, to open a cabinet that perhaps contains the radio, when the town sheriff bursts in. Oswaldo’s missing, and you now look very suspicious. You’re sent back to the hotel.

Obviously you immediately leave again, because you’re an amoral PnC character and don’t follow rules (as Harvey says himself, “and it’s the most interesting thing that’s happened in months.”) Oswaldo’s place is now guarded by a police officer, and you want to get in. We need to distract the guard, and what’s the one thing the policeman talks about? How dangerous the street crossing is just to the left. When you try to use it, cars come out of nowhere and nearly mow you down. It’s an adventure game, so you look around for objects you can reach in the limited area you can visit at this point, and find a mannequin in a dumpster, then steal some clothes from the hotel laundry (no inhibitions), and dress the mannequin to look like a person. We’re going to use it on the lethal crossing, and when it gets hit, the police officer will run over and we can go in the building!

Except, the oncoming car swerves to avoid the apparent person, hitting a sign post, the driver thrown against the windscreen, his face smashed on the bonnet, and he’s dead. Your actions just killed a complete stranger. And perhaps worst, given the context, no one saw you cause it to happen. You killed a guy, and no one’s going to be able to blame you. So… you use the distraction to go into Oswaldo’s place and find that radio.

I find this fascinating. We’re so used to that core amorality in this genre, it’s so normalised that a vaguely unpleasant person is there to be framed for our petty theft, or that we deceive a naïve person to trick them into handing over a useful item, that when our actions cause an innocent person to die… what is there to do but carry on solving puzzles? Harvey gets away with it, and immediately disassociates himself from the incident in order to progress his narrative. All except for the horrific vision that comes to him after the accident, where he sees the unknown driver’s head mounted on a wall. There are other mounted heads, all in shadow apart from one: his own. But no matter, we need to steal the nail polish from the hairdresser to paint the clay circle to look like a poker chip, so let’s crack on!

Then there are those shadowy claws, reaching into the world from above, that keep showing up in Harvey’s radio-induced flashbacks. It’s all going on for Harvey.

Some puzzles are too obvious–inventory items combined before you’ve encountered the situation where their combination would be useful, or doors held open before they’ve surprise-closed on you–while as I mentioned, there are too many moments when you’ve got a dozen locations available, but no solid idea what you should be doing next. (The in-game hints, via a notebook Harvey has, will mostly prompt you out of these, but not always, and there were a couple of times I was desperately visiting everywhere, searching for one detail.) It’s worth knowing that holding down ‘S’ will reveal interactive objects you might have missed in a scene.

But the writing and performances make up for this. This is created by Argentine team Blyts, and the English is immaculate. The actors are all top-notch too, faultless performances that perfectly capture the game’s unsettling overlap between cartoonish eccentricity and real-world severity.

The art is also stunning. It looks like a traditional, painted 2D game, and it’s only the impossible camera movements that reveal this is secretly 3D. Character animation is reminiscent of intricate paper-dolls, made dynamic by the way the camera can suddenly zoom into a scene for close-ups. It’s a really impressive look.

The result is a game that’s silly and macabre, and wants you to wonder why. It’s perhaps ironic that something that’s so smartly a piece of Brechtian estrangement also falls foul of some of the genre’s most typical issues–flaky player direction, predictable puzzles–but in some peculiar way these (undeliberate) shortcomings lean in to the meta-commentary in their own way. Oh, and be sure to stick around through the credits, because there’s a whole bunch more game to come after.

What a strange review. Hopefully most of you didn’t read it until after you played the game.

- Blyts

- Steam, GOG

- £15/$18/€18

- Official Site

All Buried Treasure articles are funded by Patreon backers. If you want to see more reviews of great indie games, please consider backing this project.

82

Charming, I assume you were trying to match the bizarre mood of the game by first writing up a walkthrough for half of the game and then saying that you hoped people wouldn’t read it before playing.

The game does have some textbook point-and-click adventure issues. We arrive at place A, pick up an item there and can’t do anything else, but place B has now become accessible (of course the game doesn’t tell us that). We go to place B and use the item there to obtain another item which needs to be used in place A. In some aspects, that kind of gameplay will always be inferior to a more narrative-driven game.

Or the game expects us to combine two items and then use the new item on an object when it’s absolutely not clear in advance what the result of those actions is going to be.

Hints are often unhelpful.

I wasn’t that much impressed with the story and the writing in general. Charming silliness and total nonsense are not the same thing.

I wouldn’t say it’s a bad game, but it’s just not my cup of tea and definitely not the best example of a modern adventure game.

Can you recommend any titles that you consider a better example of a modern adventure game?

John, you could also stress the fact that your readers can play the demo (“prologue”) of the game for free before reading the spoilery parts of your review, which are limited to the contents of said prologue (well, except for the poker chip bit). Thanks to RPS, who beat you to the punch on that one…