PC, Mac

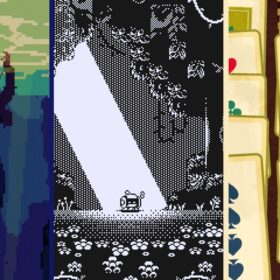

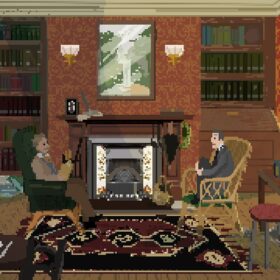

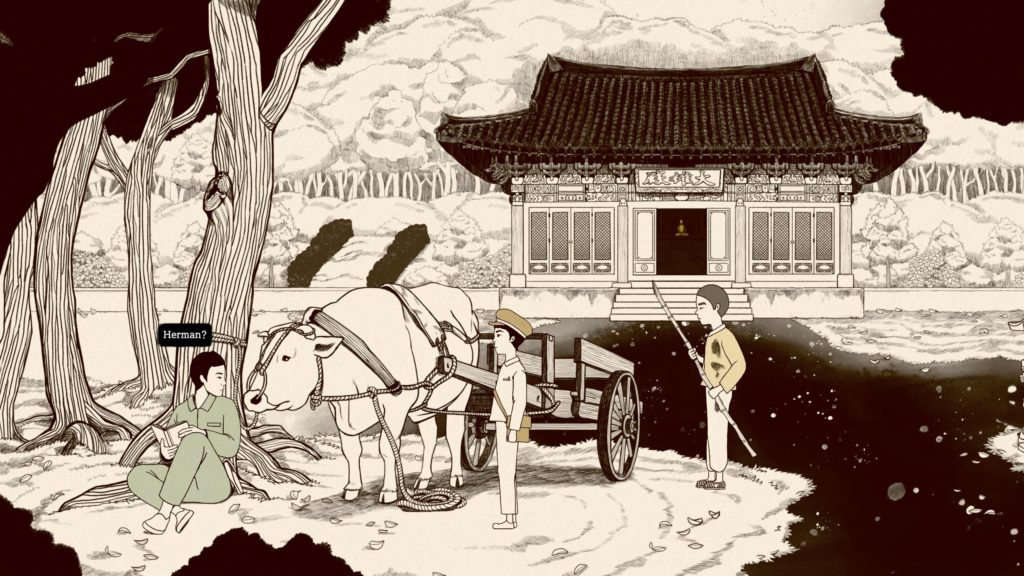

Unfolded: Camelia Tales is at once everything that’s right and wrong with point and click adventures. It frustrated me so often across its very many hours, but at the same time moved me, covering – and thus putting me at the centre of – a subject about which I knew absolutely nothing. This is the story of a 12 year old boy, Herman, living on the South Korean island of Jeju, in the late 1940s. Times were not good.

You may be far better informed than I, and already know a lot about the Jeju uprising of 1948-49. I did not. As I’ve read into it outside of the game, the depth of the horror that occurred is bewildering. Tens of thousands killed, 40,000 displaced, and war crimes on all sides. It is, on one level, no surprise South Korea wanted to prevent the rest of the world finding out, with a decades-long cover-up. On another, it likely proved to be the start of the Korean War.

I deeply love that adventure games are so often the right place to explore such extraordinarily complicated topics such as this. (Dear God, please, someone make sure Highwire Games doesn’t hear about this.) Their ability to be so incredibly focused on a single character, who also doesn’t need to be the nexus of the situation, nor indeed need to be killing people to keep things going, is very special. Whether Unfolded quite achieves this, I’m not entirely sure. But I’m so impressed it tries.

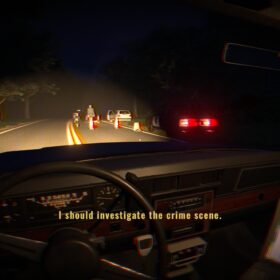

Things start off in the present day, as a couple go through the apartment of a recently deceased father, before pretty soon plunging back in time 75 years. From then on the game is viewed through Herman’s 12 year old perspective, as his village is threatened by soldiers, rebels, and who knows what.

I’m really torn between lambasting Unfolded for its reliance on some of the worst tropes of adventure gaming, and arguing that in doing so it’s far more effective in its moments of real-world horror. If the whole game were deeply focused on the atrocities, on depicting the darkness of this event, then it almost certainly wouldn’t be nearly so impactful when Herman encounters the monstrosities of humanity. On the other hand, how much do I really want to be entangled in gibberish inventory puzzles about fashioning traps to catch a pheasant in order to hear the rest?

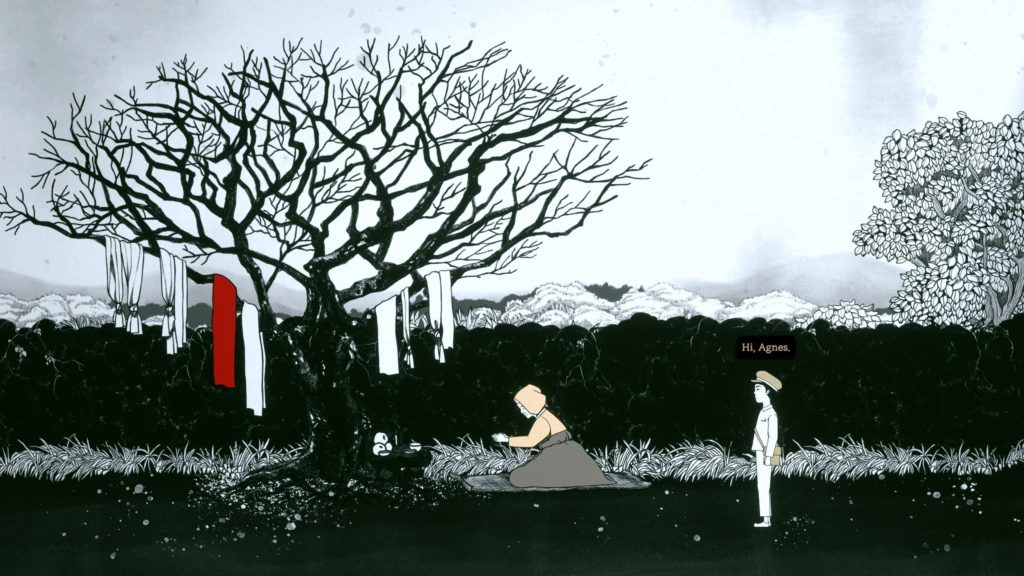

Often the two overlap in the most peculiar way, the game’s puzzle-in-puzzle-in-puzzle-in-puzzle pyramids of tasks involving finding a shovel to bury a dead comrade feeling both woefully inappropriate and utterly humanising. And there’s no question that the game’s lighthearted tone makes the moments of brutal dreadfulness all the more powerful.

However, there’s no getting around the fact that it’s also often pretty annoying. Viable solutions to puzzles are ignored, rather than written around, while solving puzzles far more often leads to another obstacle than a satisfying solution. Want to get the rice pot buried beneath the rock, but can’t because it’s too heavy? Wait, now I have a steel pole, I can use it as a lever! So in it goes and… it’s still too heavy. It was the correct answer, but it still feels wrong, because now it wants something else. This is obviously a recurrent issue in the genre, but it’s particularly egregious here.

Yet a combination of its wonderful hand-drawn art, and the fact that, wow, it’s set during an impossibly awful time, seen from the perspective of an adolescent, makes it extraordinary. It shies away from nothing, as other children become murderous monsters, and the gradual peeling back of any sense of safety by association. And while the translation is often clumsy, the quality of the writing is decent enough that it overcomes the broken English. (Still, as ever, for crying out loud indie devs, get a native speaker to go over each of your translations! There are multiple people in the game’s Steam discussions offering to do it for free, going ignored by these devs!)

There’s another factor worth raising here: the game doesn’t pull punches in terms of how its characters respond to their situation, including the very recent history of Japanese oppression. What they say makes perfect sense for a generation raised in that wake, but it still sits somewhat uncomfortably today. I think that’s fine, because it’s accurate, but your mileage may vary. And one particular poem (I forgot to say that Herman’s a poet, and by using his diary on items, he’ll compose poems about them) about a dead Japanese soldier is… awkward.

Oh, and it doesn’t end. Usually I get far more furious about this, games ending with a “To be continued” without any warning on their store page. I probably should be here too, but you know what, the game is so, so long already, and the way it ends felt pretty satisfactory to me anyway. As an open ending I’d have been cool with it, dipping into this kid’s life and then dipping out of it again. Instead, “free DLC” is planned for May, which is a damned odd choice over just delaying it – it’s not like the world was hanging on to that release date. Obviously it’s really irresponsible not to make that clear at purchase, and they should, but it’s not as bothersome as elsewhere. (Also, there’s a sizeable demo on the Steam page.)

Gosh, what a lot of caveats, issues and asides. And yet, I’ve been playing this for days and while often shouting directly at it, also being really blown away by it. It’s a mess, no doubt, but such a pretty, interesting, deeply shocking and impactful one.

- COSDOTS

- Steam

- £12/€13/$16

- Official Site

All Buried Treasure articles are funded by Patreon backers. If you want to see more reviews of great indie games, please consider backing this project.