by Sam Barker

The game boots up, some opening audio plays (I assume), and the screen displays a typical, yet frustrating message: “This game is best played with headphones.” Shit. I was excited for this one. But I’m probably not going to be able to play it. It’s a problem that happens too often, and one that goes a lot further than just PC games that recommend headphones.

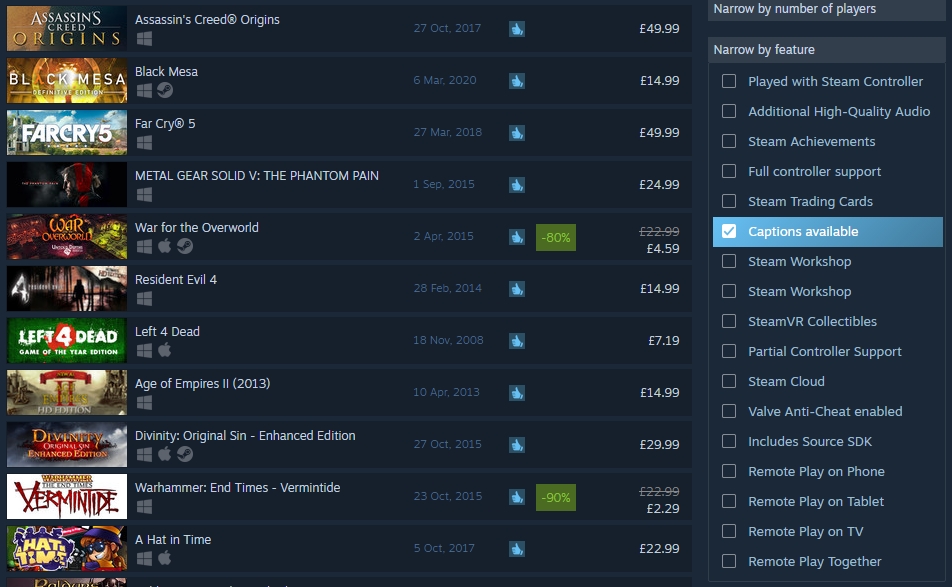

There are, in fact, a great number of ways that video games across all consoles frustrate, infuriate, and alienate deaf players. The most jarring and frustrating issue is subtitling. Most upsetting is the complete lack of any subtitles at all. (I mean come, on, seriously?) On Steam, a blank search of the games brings up 51,797 search results. 51,797 games. Scrolling down to “Narrow by feature” and selecting “Captions available” cuts that number to 1,177 – a paltry 2.3%. This may only be demonstrable of Steam’s content, and does not factor in games that contain subtitles that have not tagged that feature, but it’s still a staggering disparity. I will forever stand on the hill (although I might not die there) of subtitles being opt-out instead of opt-in. Your minor irritation at some small letters at the bottom of a screen, need not trump one of the simplest methods of accessibility.

Beyond games that lack subtitles (and games that don’t have subtitles automatically turned on so players don’t miss anything in the opening) there are plenty of other subtitling and audio issues that may not be immediately evident to non-disabled players. Too often subtitles don’t state or explain who is talking, or what a sound is/where the sound is coming from. It’s easy to lose track of who is speaking in cut-scene conversations, or miss important information that is tied to characters or objects. More than once I’ve accidentally killed the wrong person, because the game didn’t make clear who was saying what. I’ve also found myself spinning around, in game, trying to figure out where a sound or line of dialogue came from that has popped up, un-attributed, at the bottom of the screen.

Then there’s the issue of subtitles outside of cut-scenes. Often a game will subtitle cut-scenes adequately, only to leave you to wander the game world without any on-screen text at all. When raising this complaint, deaf gamers are often told that they’re not missing anything – that all the “important” dialogue has been subtitled. But this judgment between important and unimportant speech and audio inherently misses the point. Video games are not purely task-based affairs, they are experiences, and the lack of captioning for the “unimportant” audio elements of a game removes a significant portion of the experience from deaf gamers.

It’s especially significant an oversight when these uncaptioned in-game sounds and audios play an integral role in the gameplay. It could be that you’re entering a dangerous area, as in Assassins Creed Valhalla when Evior tells you an area is unsafe, without captions. It could be that something important is happening, like when a phone rings in – I don’t know – every game ever, without captions. There could be a warning from an enemy or the sound of a gun-shot, as in Fallout 4, where I have died countless times after accidentally entering a gunfight, without captions.

Sometimes these auditory cues cannot be appropriately subtitled, but rather than using imaginative alternatives like visual or haptic cues, here deaf people are largely left to fend for themselves.Resident Evil 2 is an example where, despite the game putting incredible thought and effort into the sound design, there are zero basic visual cues for the audio design and audio-specific gameplay. As such, the game’s effect is ruined. Jump scares are rendered ineffective, enemies come from out of nowhere, and the immersion is completely absent for the deaf player. But Resident Evil 2 is not alone in its lack of consideration regarding inaccessible audio cues.

In Rainbow Six: Siege, for example, there are the footsteps that forewarn the non-deaf gamers. In games like Myst there are clues baked into the music and soundtrack (something I didn’t even know until researching for this article – which I’ll take as an explanation for why I was so bad at it) (No, trust me, it’s Myst that’s bad, not you – Ed). There are the vast array of audio cues in Dead By Daylight, made all the more annoyingly inaccessible by the fact that the mobile version of the game actually does have visual indicators.

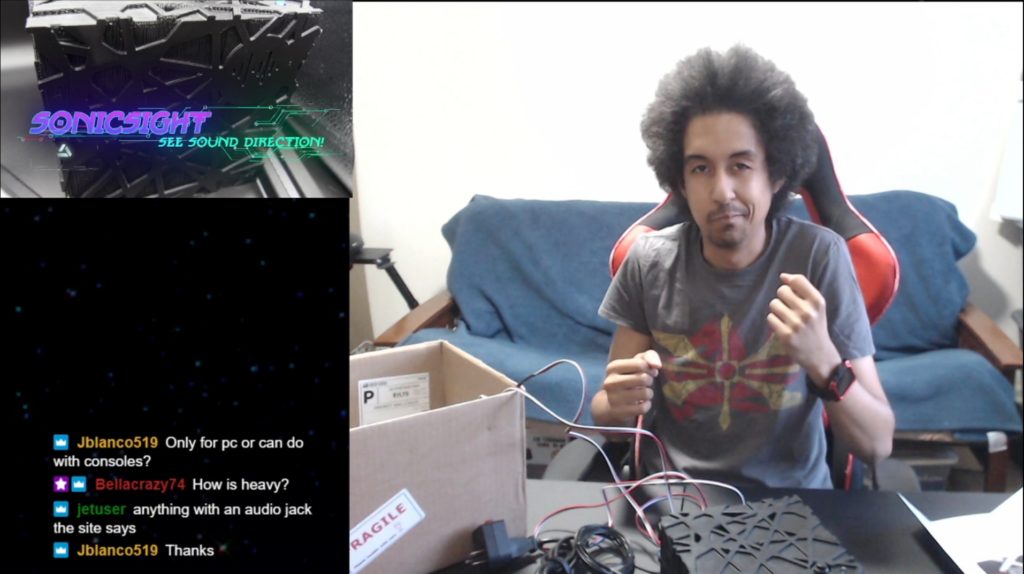

Then there’s the issue of the intense emphasis in online play on voice chat. It’s usually without a voice-to-text option, live captioning, or any alternative method of communicating. Online discussions of being a deaf gamer are rife with examples of being kicked out of an online lobby, or having other players leave a match, because of a deaf gamer’s inability to use voice chat. Often, the player doesn’t even have an avenue to explain their position due to the game’s prioritization of voice chat. In response there has been a steadily growing community of deaf streamers (such as DeafGamersTV, DM3, and Crow_Se7en) who use sign language, caption their videos, and provide transcripts. This doesn’t negate the fact that many games, particularly those popularly played online, remain inaccessible to the deaf population.

What’s common, in response to these complaints, is either a dismissal of the matter entirely, or a general gesturing from the non-disabled community towards the small library of external modifications and accessories to make a game slightly more accessible. The issue with this response is it suggests that it’s the disabled gaming community that needs to do more to be included, rather than the gaming community needing to be more inclusive. Pointing to external products, utilities and methods by which one can adapt the game to make it playable do not point out accessibility, they further demonstrate the barriers to accessibility.

All of these issues become a barrier to entry for deaf gamers into the video game world. The lack of consideration and the inability to play so many games instills a lack of desire to pursue the field.

That’s not to say there are no deaf professional gamers. There’s Fortnite pro FaZe EwOk (who was on the Forbes 30 Under 30 list), there are streamers, and there are well-known groups and clans such as World of Warcraft guild Undaunted. The success of these people in the face of the hurdles they’ve had to overcome demonstrates their own skill, but also provides a possible insight into the latent abilities of deaf gamers left out by inaccessibility in video games from the very beginning.

The wildly varying degrees of accessibility in video games is a constant source of frustration for disabled gamers. It results in a new genre of video game reviews, championed by websites such as Can I Play That and DAGERSystem, termed “accessibility reviews”. These websites and their reviews pay particular attention to the accessibility of the games in question. They critique and comment on how games consider the needs of a diverse array of gamers. CIPT’s name particularly encapsulates why accessibility should be a larger consideration for other players and the makers of the games. It’s a question that no non-disabled person has ever had to ask themselves in the same way, and a question that starkly illustrates how upsetting the inaccessibility of video games can be. It’s a simple question: Can I play that? Too often, the answer is no.

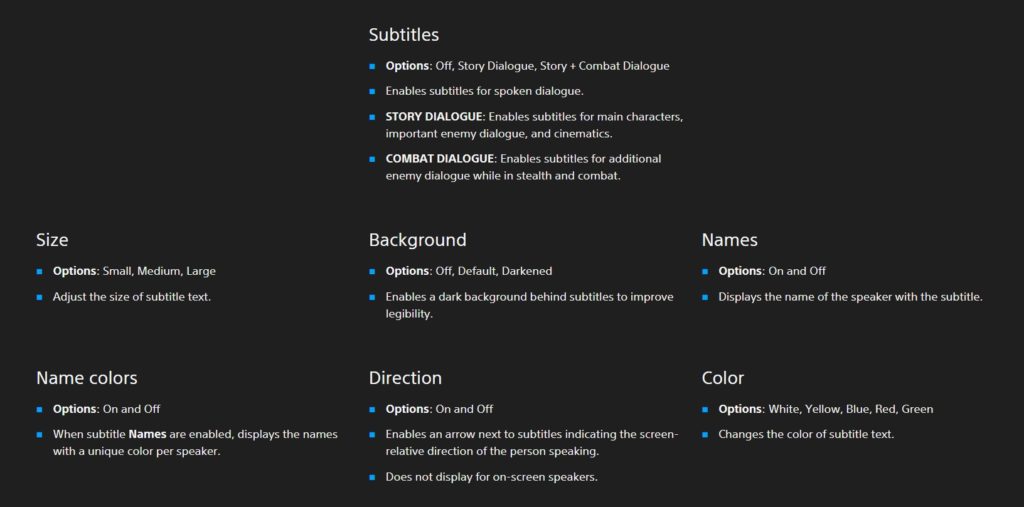

What these accessibility reviews often reveal is just how little is done, and has been done, by some of the biggest game publishers – how often disabled people have been left out of the discussion. Hearteningly, though, the reviews are also starting to demonstrate the great steps forward being taken by some. The Last of Us Part II is one example. An industry leader in the accessibility it provides, and the way these tools are integrated into the game, it represented an incredible leap forward for accessibility, where the needs of a diverse audience were understood, and considered, throughout the entire development process. From the first launch, players are presented with a number of templates they can select to help them play the game.

This choice being presented up front, demonstrates an acknowledgment of the disabled gamer that runs deeper than providing a colour-blind mode and some shitty subtitles that can only be turned on after a dig through the menus. Beyond those templates, The Last of Us Part II has a further 60-plus options for accessibility within the game menus, to really make the game as widely accessible as possible. Well-considered subtitles (of every sound and piece of dialogue) make all aspects of the audio clear to the deaf gamer. Customizable subtitle appearance solves the issue of disappearing or illegible subtitles (think white text disappearing on a white background or a cloud of smoke). Controller vibration helps with combat (the sound of enemies attacking, or an approaching object sometimes being lost to deaf gamers) and even with the guitar playing – an experience Naughty Dog did well to consider so that any gamer can truly immerse themselves in the experience of playing The Last of Us Part II.

What The Last of Us Part II illustrates is that there is a huge amount that can be done. That conversation, of whether or not accessibility can even be implemented in the first place (an offensively ridiculous conversation that wastes everyone’s time) is now moot. AAA games can be made accessible – to an incredible degree. And there’s plenty more smaller, even indie games can and should be doing. There is, of course, plenty more to still be explored. There are further roads to go down, intense heights of accessibility and representation that can still be reached, but we find ourselves now on the ground floor with a base level of understanding around accessibility. Can I Play That provides “accessibility reference guides” that cover a diverse array of needs of disabled gamers, and it’s not an insane suggestion that these should become baseline levels of accessibility across the entire gaming landscape.

Fortunately, consideration and accessibility seems to be developing at an exponential rate. Xbox, for example, recently announced the “Microsoft Game Accessibility Testing Services”, which, alongside their new accessibility guidelines, allow for critical, accessibility-focused testing, and dialogue between developers and disabled gamers. It’s a move that openly embraces the need for developers to learn more, and improve their games as a result. And, let’s be clear, it’s a step. But it is most definitely a step in the right direction.

There’s still a lot of resistance, however. In the process of writing this piece I went down a number of rabbit holes of people arguing against the implementation of accessibility in video games. Conversations across Reddit threads and in the not-so-dark recesses of gaming forums insisted, with anonymous upvotes supporting them, that, “Not everyone will be able to do everything,” and that accessibility features will be mis-used to cheat with. Misguided, sometimes aggressive statements of grandiose ableism targeted at we happy not-so-few,who just want to play some video games from time to time. And each time, I found myself returning to websites like Can I Play That and interviews such as those with Naughty Dog’s Emilia Schatz and Matthew Gallantz; bright spots of enthusiasm for the future of video game accessibility, with genuine desires, drive, and movement towards video games being accessible to, and enjoyed by anyone. Hopefully the progress being made by the big producers will bring the issue of accessibility to the forefront of the discussion around game development, and gaming in general. In doing so, it will no longer be possible to ignore, accidentally or not, considerable portions of the gaming population due to oversight. Accessibility should ultimately be as baked into a game as the mechanics, graphics, audio, and experience. To not do so will soon become a willful omission when the focus should be on games being able to be played by as many people as possible.

As a deaf man playing games, used to watching captioned television shows and movies, and participating in video calls with live-generated subtitles, it’s a strange disconnect. Almost everything else is suitably subtitled. So why isn’t this the case for games?

Samuel Barker is yet another Australian writer living in London who splits his time between bartending, procrastinating from writing, and going on increasingly unhinged rants about subtitles. More of his words can be found at unrattle.com, which he co-founded, or at barkersamuel.wordpress.com/writing/

All Buried Treasure articles are funded by Patreon backers. If you want to see more reviews of great indie games, please consider backing this project.

A fascinating article on a subject matter that interests me. Thank you for an interesting read.

I first became aware of “access” to gaming via Special Effect, a UK-based charity who primarily worked with eye and alternative controllers for gaming. I also found a Russian Youtuber (Zenko Plays) via a small comment made by John Walker on RPS, which I think was about Super Meat Boy.

Deafness and gaming is something I’m less aware of. Most recently I noticed within the Assassin’s Creed Valhalla menus they had a deaf accessibility option. I thought: “Oh great, they’ve catered for it!”, but It’s only when I read this article that I’ve realised it’s not a complete experience.

Accessibility feels like a prime area for indies to target in what is otherwise a saturated market. And I’m equally sure there are many who would be keen to read reviews by you, Sam – myself included.

Deaf accessibility is a good start, but what about limbless gamers? After a jet skiing accident I was left with no arms and no legs. I’m really disappointed by the number of games that can be controlled with mouth devices and blinking. I’d still like to game, and I’m sure there are millions of us out there. Our hundreds at least.

Why don’t game companies support us? When will John Walker take up our cause, too?

If you want to write an article about this, and what accessibility measures could and should be made, I’d be delighted to publish it.