PC

In 1439, a goldsmith named Johannes Gutenberg was working on an ill-begotten project to create polished metal mirrors designed to capture the holy light from religious relics, to be sold to pilgrims visiting an exhibition in Aachen, Germany. However, after flooding led to the event being delayed by a year, Gutenberg found himself out of money, and instead turned to his other project, a press that would use movable type to mechanise the process of printing books.

By 1450, in the German city Mainz, his first printing press was built and working, and by 1455 he was printing the Gutenberg Bible. It was only a year later that he was sued by his financer, Johann Fust, lost, and saw his work continue without him, going uncredited. He died in 1468, three years after receiving recognition for his work from the church. Between the 1460s and 1480s, the printing press went from a local business to something widespread across Germany, before spreading Western Europe-wide come 1500. This coincided with the rising of religious turmoil with proto-Protestantism, creating a threat to the Catholic rule, with the dissemination of anti-authority publications suddenly more viable.

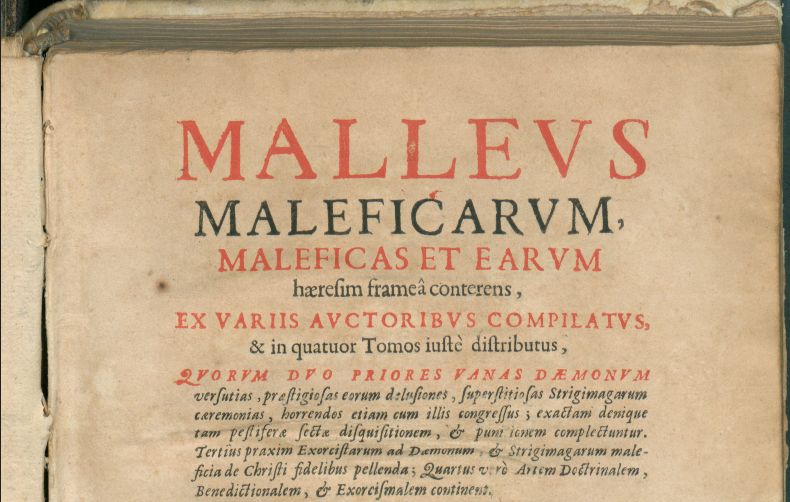

In 1486, a German Catholic clergyman and sexual pervert called Heinrich Kramer wrote a book called Malleus Maleficarum. It was a deranged and conspiratorial collection of gibberish about demons and witches, a compendium of superstitions that had built up over the last century, that suggested the only solution for all of these issues was cruel punishment and murder. A few years earlier, it might have been copied out a few times and shared among the local clergy, and – along with Kramer’s preaching – presumably inflicted a lot of harm on those in Innsbruck and the surrounding area. But given the time of its writing, the country in which it was written, and the religious unrest that was occurring all across Europe, Malleus Maleficarum went on to become enormously popular, a printing press phenomenon, its renown spreading through the 16th century. And despite the initial cries of heresy from both within and without the Inquisition, the book ignited a widespread moral panic about the dangers of witchcraft, and the need to torture and kill all who were suspected.

It of course argued that women were far more likely to succumb to witchcraft than men, tied up in Kramer’s sexual fetishes, and began the notion that a “witch” was more likely to be female. With 28 editions published over the next century, it became the accepted manual for dealing with this satanic plague amongst both Catholics and Protestants, finding this perfect storm of newfound accessibility, religious unrest, and the 15th century’s burgeoning superstitions. It would go on to lead to the torture and brutal deaths of countless women over hundreds of years – between 1400 and 1775 (the peak being the mid-to-late 16th century), some 60,000 people were executed for witchcraft, 80% of whom were women.

So, in Daemonologie you play a witch finder of the 1600s, sent to a small Scottish village to discover the identity of a local witch. Only six people remain in the village, and you must speak to them all to hear their accusations and defences, and after five days, identify who should be hanged for witchcraft.

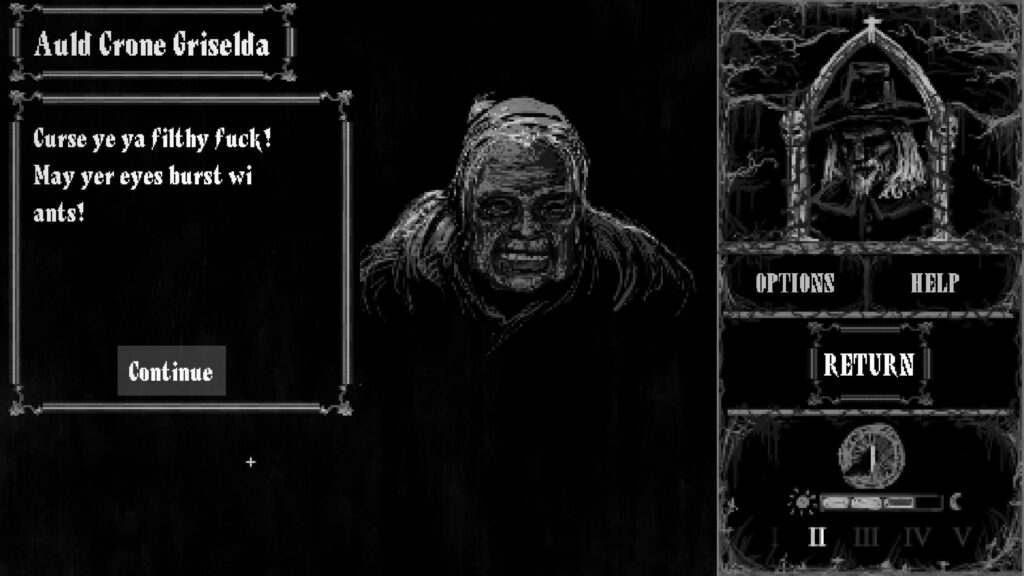

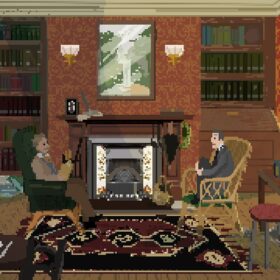

This is an astonishing game, presented in a combination of scratchy, white-on-black drawings, and hauntingly brilliant stop-motion animations, and written in old Scots. There are four days of play, in which you speak to each of the locals to hear their beliefs and protestations, and should you want to hear more information, opt instead to torture them. When you’ve unearthed four new pieces of information, night falls, and you have an astonishing stop-motion prophetic nightmares to guide you in your decisions.

There’s Maiden Lilias, who spends her time in the Ring O Stanes, a stone circle that the local priest believes in the site at which she kills babies. She, however, maintains that she’s a herbalist, like her mother, at the stones to meet her lover who is missing. Then there’s Blacksmith Oswain, in the Smiths Abode, whose jaw is held on by a wire cage after what he claims was a curse by the Shepherd Violet. She instead accuses Oswain of releasing a wolf among her flock, killing her sheep and her livelihood.

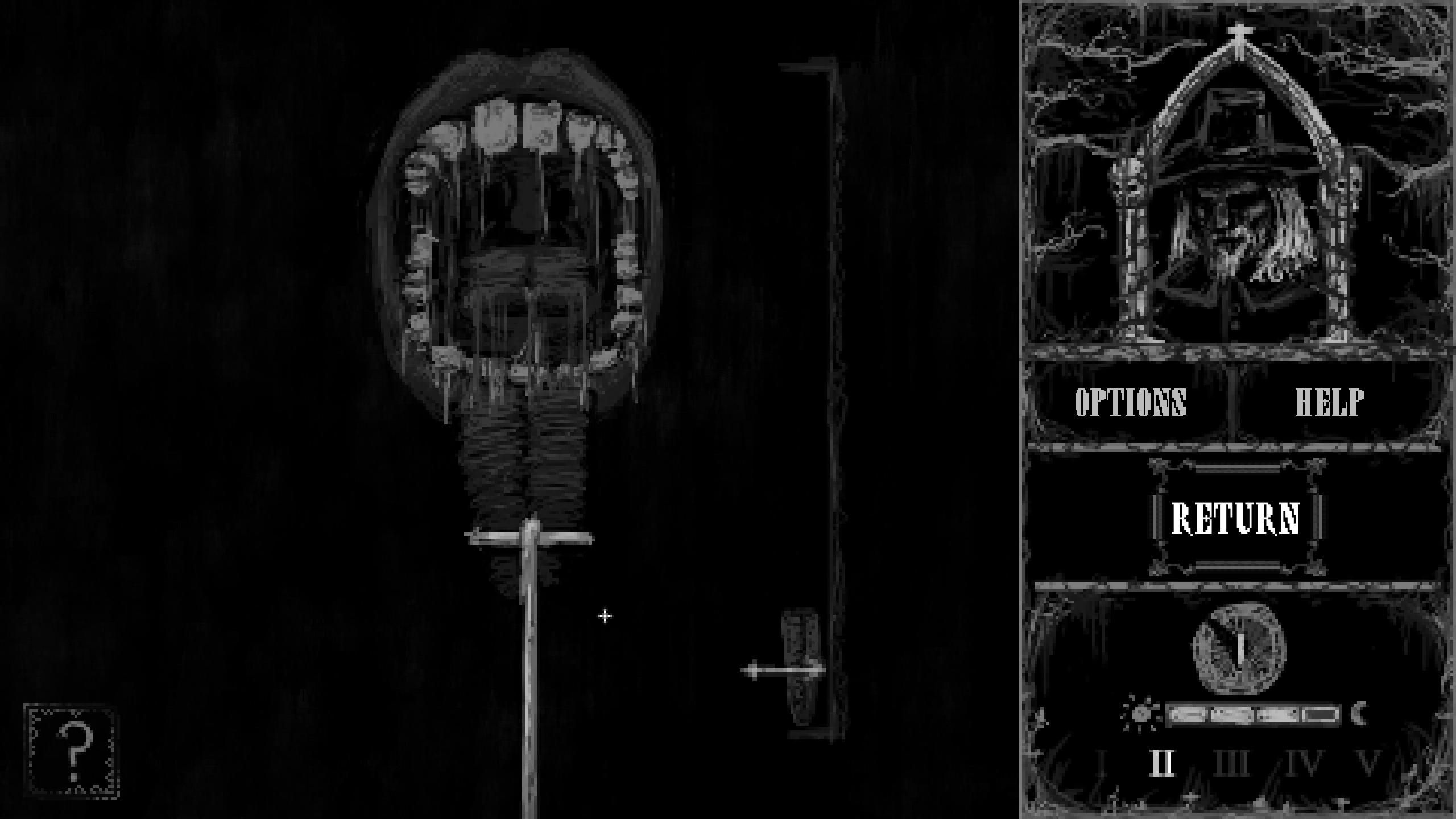

I wondered if it might be possible to finish the game without torturing anyone, given that didn’t seem a comfortable option to pick when the other choice was “Talk”. It is not. And that’s rather brilliant it turns out, given the unconscionably matter-of-fact tone the witch hunter, and in turn the game, takes throughout. Tortures play out as grotesque minigames, where you pull at a person’s tongue until it tears, without losing grip, or time mouse clicks to squeeze a person’s fingers until they’re crushed. They’re disgusting little things, like twisted versions of a golf game’s timed swings, that will cause a character to reveal information they were holding back, or even to confess.

Then, come the fifth day, you make your accusation and that person – again in the incredible, black-and-white stop-motion film – is hanged. And you leave.

This coldness is what makes Daemonologie quite so brilliant. What makes it a 30 minute game that led me to research and write this piece’s introduction, inspired by the first episode of the BBC’s fantastic The Coming Storm podcast, to understand how humanity reached such a nonchalance in the face of such deranged cruelty.

It certainly helps that it’s wonderfully drawn, with incredibly atmospheric sound and music, coupled with every line being so meticulously underwritten. And the small matter of those unnerving, sometimes horrifying stop-motion nightmares. This is all the work of one guy, Chris Evry, a passion project made in his spare time, sold for only £2.50.

The game begins with a message explaining that it’s intended to be played in old Scots English, and there’s an in-game glossary if needed, but also offers a version in modern English. If English is your first language, you don’t need the latter, believe me – it’s all easily understood, or inferred, and adds a great deal to the whole atmosphere of the game.

Daemonologie achieves so much more thanks to its brevity and its lack of an attempt to preach or proselytise. The horror is the horror, and it’s not a scary witch. That you have to be a part of that horror to experience it only makes it far more powerful.

- Katanalevy

- Steam

- £2.50 / $3

All Buried Treasure articles are funded by Patreon backers. If you want to see more reviews of great indie games, please consider backing this project.

88

I could never understand why so many games think a torture simulator would be fun to play. But even GTA had enough sense not to make it too realistic and too gruesome. This game seems to be taking it to another level.

I am also of the crowd that isn’t inclined to play a game about torturing people, but I admire the craftsmanship here. Great choice to write about.

This sounds absolutely brilliant, and awful. I’m an historian, and I love a game that can really make one feel how horrific history often was.

*spoiler alert*

What I especially love about this game is that everyone except one person is a witch and they’re all either conspiring against eachother or working together. Funnily enough, the only one who isn’t a witch is the only one that doesn’t really look human. I’m not sure if this is metaphorical or satirical or simply just a random detail but it’s interesting nonetheless. Another detail that’s is particularly interesting is that it truly does not matter who you accuse of being the witch in the end as the character you play as still gets paid and is thus satisfied with his work regardless of the choices he’s made.

I would love if this game had more content and a more in-depth storyline but the way it’s written is brilliant nonetheless.